CHARLIE ELLIS WANDERS BESIDE THE WATER OF LEITH

The relationship between art and nature is evident on the Water of Leith. This is expressed most obviously through Anthony Gormley’s figures but also in the ‘accidental’ art forged by the surge of late December, which saw torrents of water cascade through the river's gorges and under its bridges.

It caused damage (much of it now repaired, with work parties from the The Water of Leith Conservation Trust to the fore) but also left behind interesting, serendipitous sculptures. These included the Wicker Man style ‘thing’ which embraced the railings near Tanfield.

Just to the west of Dean Village, a tree, ripped from the bank, lies disconsolately in the river, its voluminous roots forming a dam across half of the width. As an accidental work of art, it demonstrates how fragile and powerful nature is. In time, the tree will be eased from its moorings and sent tumbling over the weir to bemuse the instagramming tourists gathering around the bridges in Dean Village.

‘The forbidden zone’

For several years this spot (below Dean Path) constituted the boundary of Edinburgh’s ‘forbidden zone’. A series of landslides caused this section of the walkway to be closed, though many braved it in clambering over and round the obstacles. Knowing looks were shared by the ‘scofflaws’ who ignored the signs and flouted the rules.

Following extensive work, this section has reopened. The repaired bank has been reclaimed by nature, though the austere wall at the top has definite echoes of Potsdamer Platz circa 1981. At one corner of the zone, an informal art installation now sits. This includes a bench, currently painted in the colours of the Ukrainian flag. The flecks of red paint around here seem to be a comment on the lives lost in the last year of brutal conflict.

Spring in the step

I passed here last week on the way to the Gallery of Modern Art. Along the river bank, the first signs of nature and growth are emerging. Snowdrops litter the banks in many places, while the first shoots of wild garlic are evident, though its pungent aroma has yet to fill the still chilly air. I look forward to blitzing it into a delicious pesto in the months to come.

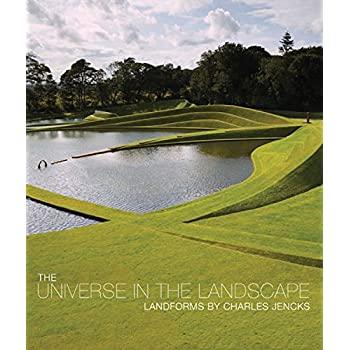

Outside Modern 1, Charles Jencks’ Landform Ueda was receiving its first trim of the year, the smell of freshly mown grass another sign of spring approaching on the calendar, if not in the air. The pallid grass revealed by the blades of the mower indicates that vigorous growth is still to take place.

Unlike the fallen tree in the river, Landform Ueda was designed and manmade. Inspired by nature it is increasingly being further 'naturalised' by its environment. Its condition and colour reflects the seasons. At present, it shows signs of winter scarring, which will take till mid spring to heal. Will summer bring a discolouring drought or verdant growth?

‘Conversations with the Collection’

Inside, the ground floor of the gallery is being readied for new exhibitions. The focus is on ‘Conversations with the Collection’ upstairs, which builds on exhibitions of previous years. It features a number of works that are rarely seen by the public. The recent report of museum artefacts are ‘gathering dust’ shows how much fantastic material spends its time in storage in such cultural institutions.

‘Conversations with the Collection’ brings some artworks out into the open. The varied and rich exhibition is almost too much to absorb in one viewing. Though broken up into loose thematic sections, you are sometimes besieged by what you encounter in every room. The juxtapositions are arousing; the unexpected connections intriguing.

With the themes of nature in my mind, my eye was caught by a stark poster of Joseph Beuys’ 7000 Eichen (7000 Oak Trees) project. A manifestation of his idea of ‘social sculpture, of art’s potential to challenge and transform society. It’s one of the key features of the ‘Creative Terrains’ segment of the exhibition which focuses on the relationship between humans and the natural world.

The original 1982 project centred on a plan to plant 7000 oaks throughout the city of Kassel, pairing each with a piece of basalt. He chose the oak because of its longevity and because the tree ‘has always been a form of sculpture’. As each tree was planted, the pile of stones diminished. A living, growing object replacing an unchanging ‘crystalline mass’. The project helped to illustrate the excesses of urbanisation and sought to help alter the living space of Kassel.

What it helps reveal is that, in many cases, the artistic imagination engages with themes which most have not even identified, let alone explored. Artists as social pioneers in some sense, testing the boundaries. Beuys was a pioneering environmentalist and a key figure in the formation of the German Green party. His political and artistic visions were fused, not compartmentalised. Many of his themes of the 1970s and 1980s are now thoroughly mainstream.

Free trees in Inverleith Park

As an illustration of the way that Beuys’ ‘avant garde’ work has entered the mainstream, today I receive a notification of ‘free trees’ being offered at Inverleith Park. It’s part of a ‘million tree city’ project, involving Edinburgh and Lothians Greenspace Trust and Woodland Trust, which seeks to further enhance Edinburgh’s greenness.

On Saturday (4 March), trees will be available to collect from Inverleith Park between 10am and 2pm. I’m sure that Beuyss would approve of such ‘participatory’ activity and the way it causes us to look beyond our own lives. As he put it, ‘once the tree grows tall, the planter will be long gone .’

‘Conversations with the Collection’ continues at Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (Modern One).

Charlie Ellis is a researcher and EFL teacher who writes on culture, education and politics.