FLOUR, MURDER AND THE WATER OF LEITH

Pamphlets have been part of our culture for hundreds of years. The religious controversies of the early 16th century saw the first great age of pamphleteering. Our political culture has been shaped by pamphlets, from revolutionary tracts to the output of influential think tanks such as the Institute of Economic Affairs. Today, these organisations regularly publish the words of ‘policy wonks’ in this form, even if most read them as PDFs rather than austere A5 booklets.

An interesting attempt to revive the form was the Chatto Counterblast series of the late 1980s and early 1990s. These featured ‘Britain’s finest writers and thinkers’ (such as Mary Warnock, Christopher Hitchens and Fay Weldon) confronting the ‘crucial issues of the day’. The pamphlet form allowed the authors to extend their argument beyond the typical comment piece, while focusing on a single theme.

The pamphlet form remains popular in the poetry world. It suits the minimalist form. Citadel Books in Abbeyhill has a particularly good selection. In a lecture (itself reprinted in pamphlet form) by Richard Price of the British Library, he talked of ‘Poetry Pamphlets as Public Private Space’. Though pamphlets were found in various sections of the Library, he did feel that poetry and pamphlets were ‘natural partners’.

Someone I know well who sells books online relates that pamphlets are the most fruitful category they have. Their specialist nature and limited print runs mean that people are prepared to pay good prices. Their slimness means postage and packing costs are minimal.

I’ve long been a fan of the pamphlet form. As Price notes, they are ‘modest’ in their physical form but can contain great ‘curiosity, comedy and pleasure’. They are inherently ‘minimalist’, free of padding. There are many books which would be better as pamphlets. Their length means they are a great way to absorb knowledge. They are usually one-off printings, so they’re often products of their era. This can provide an insight into the period in which they were produced. For example, many local-history pamphlets were typewritten, while those from the 1990s bear witness to the rise of the word processor.

Rather grand in spate

I recently picked up a nicely faded pamphlet on the Water of Leith, written by Robert Croall. A well written pamphlet, it eschews excessive detail, concentrating on the river and its ‘environs’. Though with a particular focus on the baking industry (Croall’s other works included ‘A Short Account of Baking in Edinburgh’), the pamphlet is of general interest. Published in July 1960, it’s punctuated by some lovely evocative adverts from the time; for yeast, chocolate couvertures, and other catering-related products.

The text takes the reader down the length of the river, which ‘flows feeble in summer but rather grand in spate’. The torrents which flooded pathways and basements in late December were a reminder of the power of the river when ‘in spate’. To catch a glance of thundering ferment, onlookers peered over ledges and bridges and inched towards precipices. It battered and severely damaged the metal bridge at The Britannia Hotel, Belford, and engulfed Antony Gormley’s metal men. Repair work has now begun on that bridge and ‘all being well’, will be completed by 17 February. That seems an ambitious target. Gormley’s figures have now lost most of the flotsam and jetsam that attached itself just before the turn of the year.

I recall venturing out on 30 December and trying to use the Rocheid Path to get to Inverleith. I was met with the sight of a man forced to use the fence as his means of keeping clear of the inundated walkway. There was no way through. In the days after, the amount of debris and damage along the river was startling. Particularly ‘impressive’ was the area around Tanfield, where it looked as if an abstract artist had been at work, sculpting assorted twigs and grass into something quite startling.

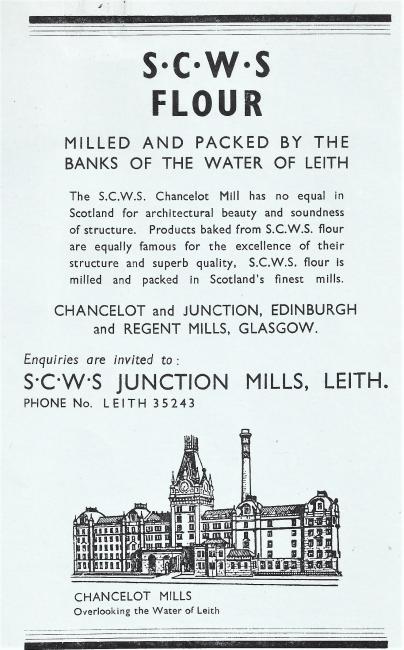

Croall’s description of the river and its environs remind us that at that time, the river retained a highly industrial character, with several mills still active. In particular, there was Chancelot Mill, which features in an elegant advert for SCWS Flour, ‘milled and packed by the banks of the Water of Leith’. Its building apparently had ‘no equal in Scotland for architectural beauty and structure’. The area around St Mark’s Park where it stood is currently in the process of radical change as the Powderhall Waste Centre site is developed.

Not dark yet but it’s getting there

Croall’s narrative is nicely punctuated with slivers of poetry and literature. This enriches the narrative and emphasises the number of writers who have been drawn to the river and inspired by it. When it reaches Spurtleshire, the narrative gets stranger and the recollections darker.

Croall talks of the ‘very pretty sequestered’ village of Silvermills which was apparently ‘much favoured for many lovers’ trysts and rambles’. Silvermills is another area being redeveloped, with piles of bricks peppering the area around Henderson Place Lane. I wouldn’t imagine this is an ideal environment for the ‘trysts’ Croall speaks of.

On to Canonmills, where Canonmills Loch was, in 1682, the ‘scene of spulzie, and riot’. Apparently, ‘the tacksman of Canonmills, Alexander Hunter, not only destroyed the paper mill belonging to Peter de Bruis, but [also] flung Peter’s wife into the dam’. The 17th-century version of Edinburgh Live would be pumping out clickbait articles on this for weeks!

Croall goes on to recount a ‘great tragedy’ at Warriston House https://canmore.org.uk/collection/1469283 (demolished in 1966) in 1600. It involved the beating to death of the Laird by his servant, ‘prompted by the Laird’s selfish and cruel wife’ and her nurse. The nurse was subsequently ‘burnt at the stake on Castle Hill’ and Lady Kinaird beheaded in the Canongate. Again, I sense that were this to happen today, a 4-season Netflix series would be forged from the dramatic story.

I certainly hadn’t expected to be transported in this way when I picked up the slim, faded pamphlet. What the pamphlet does remind us of is the rich history of the Water of Leith and the great value it adds to the city. As Croall concludes, ‘the good folk of Edinburgh and Leith, will always hold the water dear to them through the ages … Its future is assured, because men cannot successfully efface Nature, and stop her progress.’—Charlie Ellis