EDINBURGH MUNICIPAL AFFAIRS

[CONTRIBUTED]

In considering the various schemes on which the Town Council have embarked, and the result of their operations, it has to be remembered that all municipalities in the country have of recent years undertaken a great many new functions, and that great difference of opinion has existed, as to whether they were right or wrong in doing so.

Edinburgh has only gone with the flowing tide of municipal inclination in what it has done, and it would be useless to discuss now whether it should have entered into a great many of the undertakings to which it is committed. It is certain that some of them were necessary, and the question rather is, how have the Town Council carried them out? In dealing with this matter the simplest way will be to discuss the schemes in the order in which they appear in the Police Accounts.

[…] Last year a second wash-house, situated in that new Arcadia, the Allan Street, Stockbridge, reformed slums area, was opened, and produced a revenue of £53 at a cost of £232.[1] Those figures seem to bear out what one would have expected, that in Edinburgh, where the sanitary authorities require water to be conducted to every house, there is no necessity for public washhouses.

The construction of the Allan Street washhouses was a gross piece of extravagance. They were put down where a slum area had been cleared away, and where ranges of new houses with all modern requirements had been erected by a benevolent municipality at the cost of the ratepayers. The construction of these wash-houses at Stockbridge has been going on for some time, and during last year the capital expenditure on them was £3500. The interest and sinking fund on the cost have, of course, to be added to the loss in conducting them before the amount which is charged on the rates can be ascertained.

It is to be sincerely hoped that there will be no more expenditure on public washhouses in Edinburgh. The best thing the Town Council could do would be to sell the two they have at present, and avoid further loss. […][2]

Scotsman, 29 September 1903

[1] The first washhouse had opened in South Gray’s Close in 1899. Contrary to the the Scotsman’s assertion, the Allan Street washhouse had opened in January 1903, the same year in which this article was published.

[2] In 1908, superintendents of the public baths and washhouses in Edinburgh reported to the Plans & Works Cmte that, in the year ending 15 May, there had been 23,475 washers at Allan Street, averaging 83 per day. The revenue was £428. Source: S (12.6.1908).

*****

AN EDINBURGH WIFE-BEATER GETS SIX MONTHS.

A middle-aged man named Richard Alcorn, a bricklayer, pleaded guilty before Sheriff Rutherfurd at a Pleading Diet of Edinburgh Sheriff Court to-day, to having, on 23d September, in a house in Greenside Row, then occupied by him, assaulted his wife, beat her with a poker, and kicked her, fracturing one of her ribs.

An agent stated that accused had received great provocation. When he went home from his work there was no food in the house, although he had given his wife money with which to procure it. The accused, it was stated, was sober, but his wife was under the influence of drink.

The Sheriff characterised the assault as a very serious one, and remarked that it was aggravated by the fact that it was committed on his wife. Accused had been twice previously convicted. Taking into account the fact that there had been considerable provocation, the Sheriff limited the sentence to one of six months’ imprisonment with hard labour.

Edinburgh Evening News, 5 October 1903

*****

TRAGIC DEATH OF AN

EDINBURGH ARTIST.

FATAL FALL IN THE STUDIO.

A tragic occurrence, involving the death of the well-known Edinburgh artist, Mr Joseph Thorburn Ross, A.R.S.A., 6 Athol Crescent, is at present engaging the attention of the Edinburgh City Police. The circumstances of the sad affair are at present wrapped in uncertainty, although a likely theory is put forward, and meanwhile, at any rate, reticence is being observed among the authorities, which makes it difficult to elucidate much definite information.

As far as can be ascertained, however, it appears that Ross resided with his sisters at 6 Atholl Crescent, where his studio is also situated. The ladies are at present away on holiday, and since his return from his own holidays, about three weeks ago, the artist had been residing alone in the house, with the exception, of course, of the servants.

On Saturday night he had to dinner with him a friend and fellow-artist,[3] and the two gentlemen remained together until well on in the evening, chatting and smoking in the house. When his friend rose to go, Mr Ross put on a cap and said he would accompany him part of the way home and get some fresh air. Accordingly, the pair set out together, but when they had gone as far as St Patrick’s Square, Mr Ross suddenly remembered that he had some brushes to steep, and, intimating this to his friend, he bade him goodnight and retraced his steps.

He was not seen again, and when a servant went to his room to awaken him next morning, she got no answer to her knock, and, entering the room, found that the bed had not been slept in. She informed her fellow-servants, and after talking the matter over they came to the conclusion that Mr Ross must have slept at his friend’s house, and would return during the day.

As the hours passed, and there was no appearance of their master, the servants became uneasy, and when night came with still no sign of him, they gave information to the police. The latter at once placed communication with Mr Ross’ friend, and ascertaining that the missing gentleman had on separating on Saturday night intimated his intention of returning to the studio, the officers at once proceeded there.

The door of the studio was locked but it was burst open, and doubled up behind the door, and in a semi-unconscious condition, they found the missing artist. His clothes were unloosened and dusty, and a hasty examination showed that he was suffering from a severe wound on the temple, while his right ankle was broken and bleeding.

A cab was at once secured, and the injured man was removed with all possible haste to the Royal Infirmary, where he was attended to by Dr Gilford, and placed in No. 7 ward. He was semi-unconscious and delirious, and, despite all that could be done for him, gradually sank, and died shortly before seven o’clock this morning.

At first sight the affair appeared to be of a mysterious character, especially having regard to the fact that the studio door was locked, but an examination of the studio provided a likely solution of the mystery. Surrounding the studio is a balcony, access to which is by a stair, and it is believed that Mr Ross had occasion to go to the balcony, possibly to see if the gas was properly turned on at the meter, which is on the balcony, and ascending or descending the stair he apparently slipped and fell to the bottom. When he partially recovered consciousness he endeavoured to crawl to the door to call the servants, but was unable to summon sufficient strength, and lay there until found.

THE SCENE IN THE STUDIO.

Inquiries made at the house at 6 Atholl Crescent elicited further details of the tragic occurrence. It appears that a few weeks ago Mr Ross’ two sisters left for Kircudbright on a holiday, and the deceased and two servants remained on in the house. On Saturday evening he was visited by W. M. Mackenzie, fellow artist and close friend,[4] who resides at 5 Duncan Street, and they spent several hours together, Mr Ross being in the highest spirits.

Shortly after ten o’clock Mackenzie left to go home, and Mr Ross agreed to accompany him part of the way. The servants waited up some time for their master’s return, but when it became late they assumed that he had entered his studio from the lane at the back and retired. On Sunday his absence did not cause them uneasiness as they believed that he had gone out to spend the day in company with some of his friends, and it was not until last night that they became alarmed.

Knocking on the studio door several times, and receiving no answer, one of the servants summoned a policeman, while the other proceeded to the house of Mr Mackenzie, who at once returned to Atholl Crescent. When he arrived the policeman set about obtaining entrance to the studio, which lies at the back of the house, a green intervening, and a small window provided the easiest means.

The sight which met the constable’s gaze was a startling one. Bleeding from several wounds, and with his clothes disarranged and covered with dust, Ross lay huddled in a heap at the foot of stair leading from the studio floor to a balcony which runs round the studio.[5] He was in a semi-conscious condition, and was able to smile to the servants, who, as can be well understood, received a great shock. Mr Ross, however, was past speaking, and, recognising the gravity of his condition, the policeman and Mr Mackenzie lost no time in having him removed to the Royal Infirmary.

The servants state that when he left on Saturday night with Mr Mackenzie, Ross was in the best of spirits. There was no indication then or at any time previous of anything unusual in his behaviour, and it never occurred to them that there was anything amiss until pretty late on Sunday evening.

STATEMENT BY MR MACKENZIE.

Interviewed this morning, Mr Mackenzie was able to throw sufficient light on the occurrence to dispel the air of mystery.

He stated that they left the house in Atholl Crescent on Saturday night about 10 minutes past 10, and walked slowly along Princes Street and up the Bridges. At St Patrick Square they parted, Mr Ross remarking that he would hurry home as he had some brushes to steep.

Last night, about ten oclock, he was surprised to receive a call from one of Ross’ servants, who asked him to proceed without delay to the house in Atholl Crescent, as something had happened to Ross. On arriving at the house he found a constable waiting and together they decided to force an entrance into the studio.

They got in by a window, and were horrified to find Mr Ross lying in a state of utter collapse. Blood was flowing from his mouth, there was an ugly wound on his forehead, and his clothes were covered with dust. There are two entrances to the studio, one from Atholl Crescent Lane, and the other from the green, which divides it from the house. Mr Ross always kept possession of the keys, and from the position in which he was found, and the fact that the servants had heard no sounds, the supposition is that he must have entered by the back door.

At first sight appearances were apt to suggest that there had been foul play, but on closer examination it was found that Mr Ross had taken off his boots and collar and tie, and that both doors were locked from the inside. He lay on the concrete floor of the studio at the foot of a stair leading to a balcony, on which the gas meter is placed, and though able to recognise those around him, he could not for a time speak. Before being removed to the Infirmary, however, he was heard to murmur, in reply to a question by Dr Steven, who was called, that he had fallen on the concrete floor. That was the only statement that could be got from him.

The probable explanation of the sad occurrence is that Ross had on entering his studio on Saturday night mounted the stair leading to the balcony in order either to turn on or off the gas, and had fallen.[6]

[The] deceased artist returned about a fortnight ago from a holiday at Stonehaven, where he was the life and soul of the company in which he mixed. Among artists his genial disposition made him a general favourite, and the news of his tragic end will be received with deep regret. Mr Ross was unmarried, and about 40 years of age.[7]

ROSS’ ARTISTIC CAREER.

Joseph Thorburn Ross is a son of the late Mr R. T. Ross, R.S.A. He was brought up in an artistic atmosphere in the house in Queen Street in which he was born and spent his boyhood, and this atmosphere affected the family—his elder brother, who went to America, and his sister, Miss Christina P. Ross, who is well known not only as a good water-colour painter in the city, but a successful teacher.[8]

Quitting commerce, Mr Ross took to paint with enthusiasm from the start. His first experimental ground was the Severn and district, and there he and his comrades led a delightful gipsy life, combining sketching with rowing, swimming (in which Mr Ross was an expert), and walking. Among other adventures, he and his friends crossed the Bristol Channel in a cockle-shell outrigger.

A period of study followed at the Art School in Gloucester, where his master was Mr John Kemp, to whom, as well as to Mr T. Gambier Parry, Mr Ross was much indebted. From Gloucester Mr Ross proceeded to Paris, and thence to Edinburgh, where he studied the antique, under the tuition of Mr Hodder, and was gold medallist for his year. The life class of the R.S.A. followed, and Mr Ross was now working for the first time in oils, under the supervision of Mr Clark Stanton, R.S.A.

His course ended there, Mr Ross set out to travel, and not many of the younger men could boast of so wide an experience in foreign parts as he had. He was frequently in Holland, and Belgium, and France, the remoter nooks of which had great attractions for him; he had been in Spain; and in Venice, Verona, and Bruges he was as much at home as in Edinburgh.

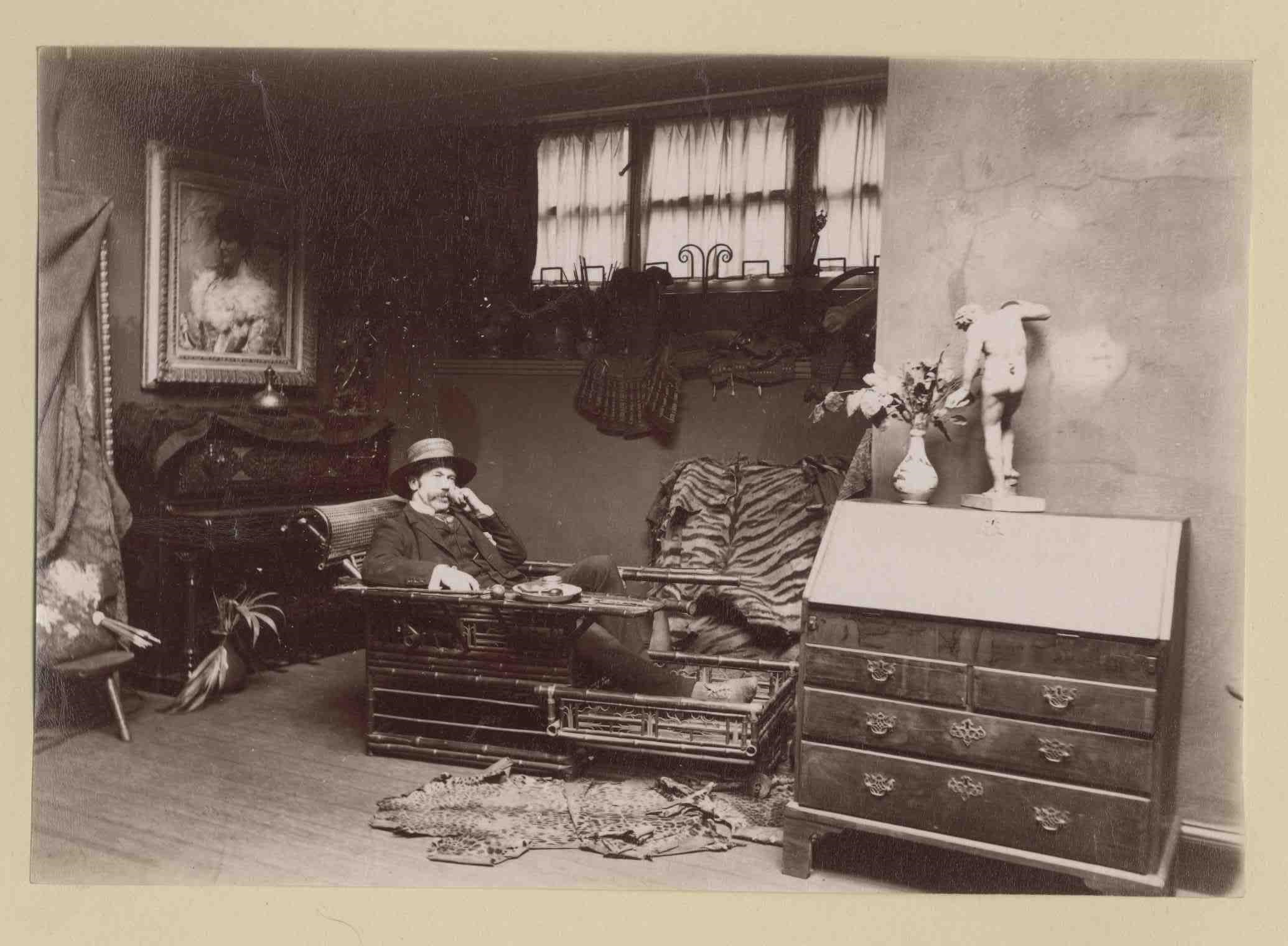

Mr Ross was a delightful personality. To know him was to love and respect, and there was no more popular figure in the art circles of the city than Joe Ross, the name by which he was familiarly known. As a painter he was full of surprises. Anything but conventional, one never knew what to expect from him; he was always breaking out in some new line. His largest pictures were painted some years ago, and several showed that touch of genius which led people to be always on the outlook for the “chef d’oeuvre” that would take the art world by storm. His subjects were various, his execution at times brilliant, but there was on many occasions a touch of the bizarre that transformed what might have been a success.

Among his leading works were: “A Garland of Poppies,” exhibited in 1889; “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” in 1890; “Where do the Fairies Dwell,” in 1891; “Serato Veneziana,” in 1892 (a work that won a diploma of honour at Dresden and was reproduced in Berlin); “A Daughter of the Soil” and “The Poppy Field,” in 1894; “The Beau of the Hiring Fair” exhibited in 1900; and a very imaginative view of the Bass Rock, with seafowl, shown a couple of years ago. He was a striking colourist, and a capital painter of the figure. Mr Ross was elected A.R.S.A. in 1896.

Edinburgh Evening News, 28 September 1903

[3] William Murray Mackenzie, artist (active c.1850–1908).

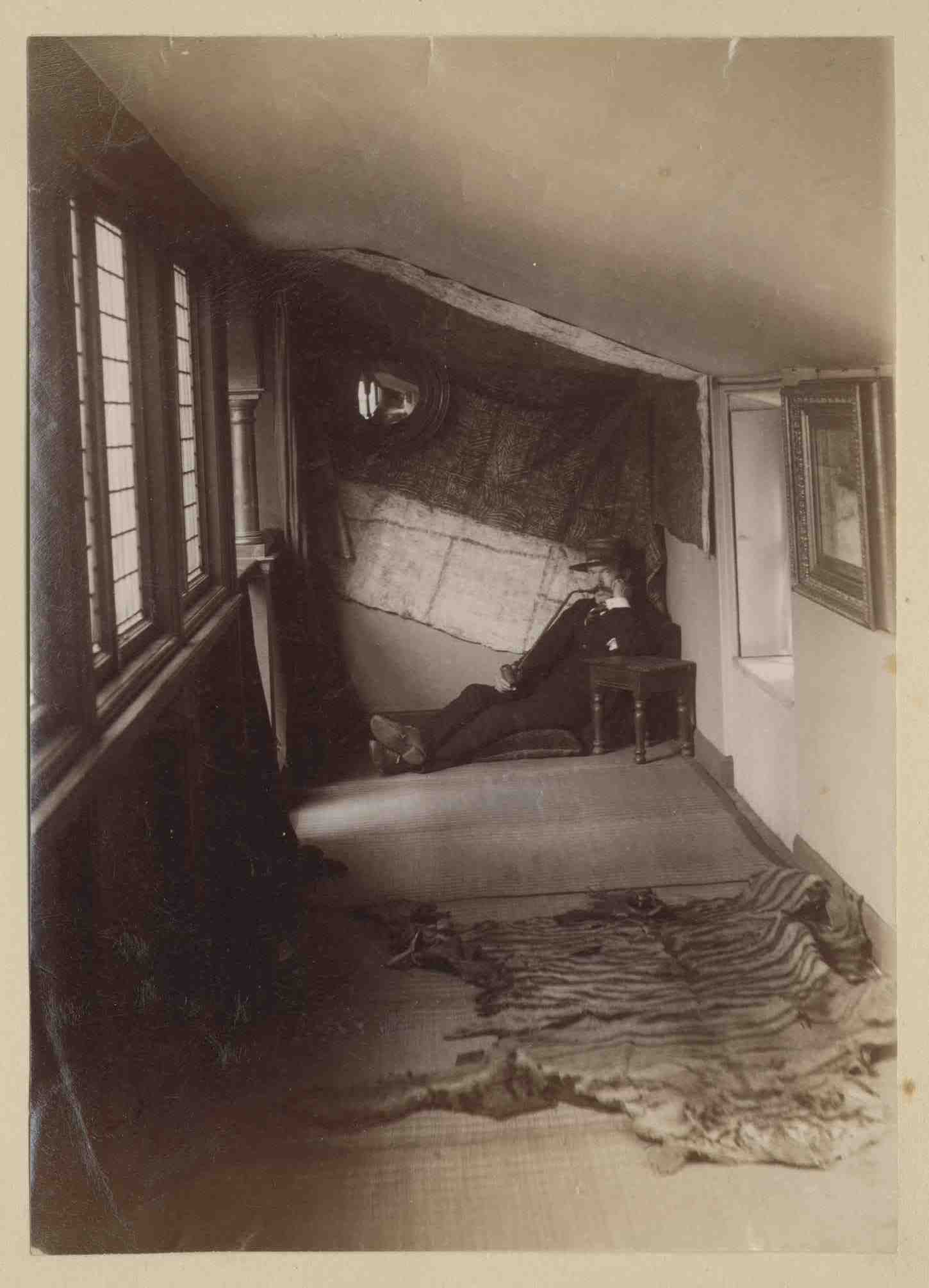

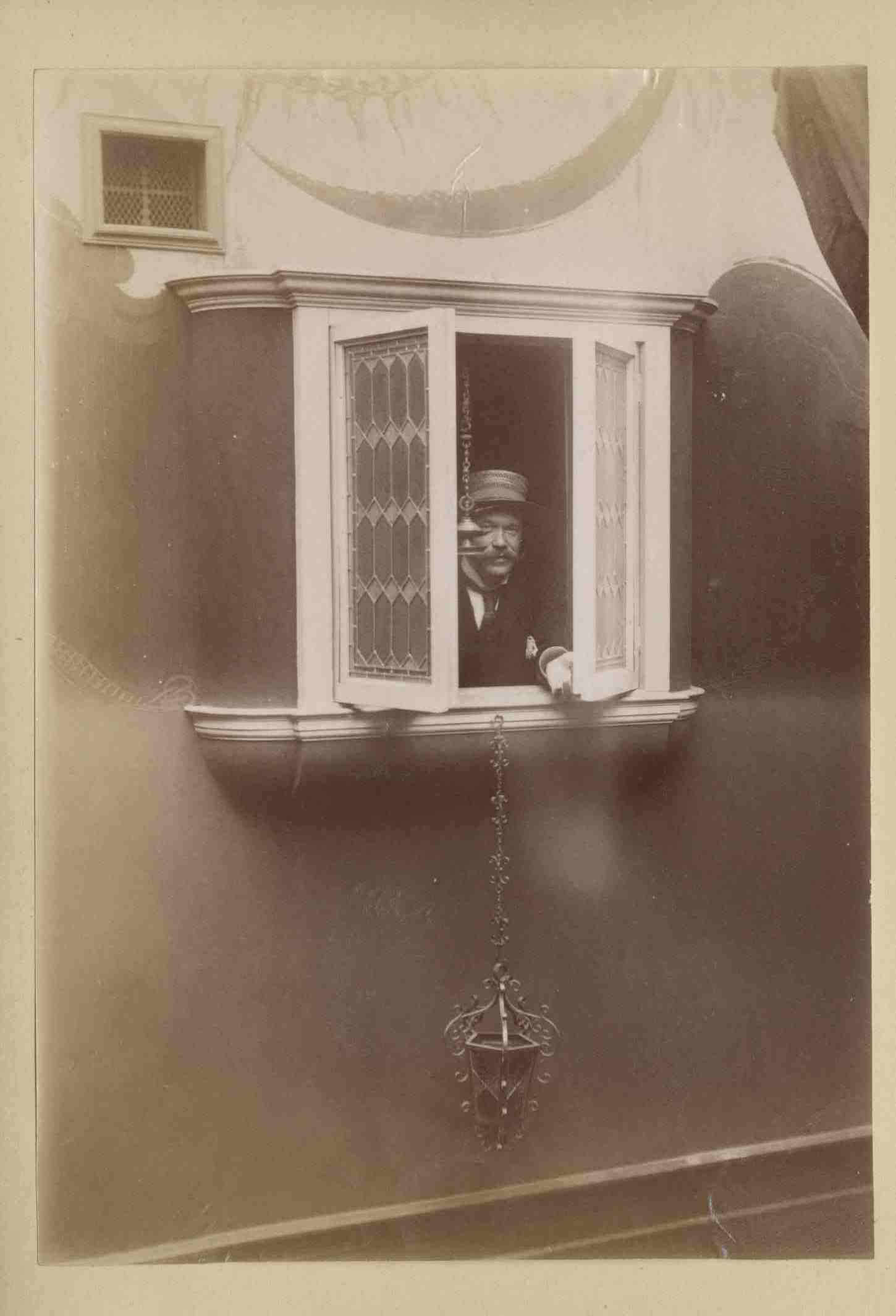

[4] S (29.9.1903) added: ‘The studio, it should be explained, forms one of a range of buildings in Atholl Crescent Lane, which had been originally built as stables for the houses in the Crescent. Each has a direct communication from the land, and also a door opening on the back green of each house. Mr Ross some years ago had this stable entirely cleared out and converted into a most artistic studio, with top light and all other requisites for painting. At one end is an ingle nook, and over it he had built at a height of twelve or fourteen feet a balcony, which was also carried round the south wall of the studio. This was reached by a closed-in stair, rather steep in the pitch, and with polished wooden steps. Mr Ross was a great athlete. He had a trapeze and horizontal bar fitted in his studio, and he delighted in keeping himself in condition by their use. Often he had friends in his studio, and the balcony formed the place from which the athletic exhibition given on the floor below could be viewed.’ The building has since been demolished and replaced.

[5] S (ibid.) elaborated: ‘On examining the studio it appeared that Mr Ross must have let himself, as he often did, into it by the lane door, which he had locked behind him. He had taken off his collar and tie and his boots, and had put on a pair of white canvas slippers. He had carried out his intention of washing his brushes, for they were all found clean and in order. It is likely after that that he would take a turn on the horizontal bar, which was found in position for exercise. The gas meter is, it seems, situated on the balcony, and it is conjectured that he had ascended to screw off the gas, and in returning had stumbled and fallen headlong down the stair. One slipper was picked up half-way down; while the other was still on his foot when he was found. What makes the accident doubly painful is that the poor sufferer had lain in his blood the whole of Sunday, unable to call for assistance, and with his life slowly oozing away.’

[6] In fact he had been born in 1849 and was a well-preserved 54 at the time of his death.

[7] For more on the life of Ross and his family, visit 'Berwick Timelines', last accessed 23.11.20.

[8] Painted portrait: Joseph Thorburn Ross, ARSA, by his father Robert Thorburn Ross, 1873 (Royal Scottish Academy).The sepia photographs shown above are thought to be of Ross in his studio. They are held in the collection of Lauriston Castle, and are reproduced here by permission of Edinburgh Museums. See Helen Edwards, 'Auld Reekie Retold', accessed 2.05.21.