COULD FAG END OF FEUDALISM BREATHE NEW LIFE INTO AULD ALLIANCES?

When the United Kingdom exited the European Union on 31 January 2020, many Scots who had voted in the Referendum to remain thought the advantages of EU membership had gone forever.

Now, however, new scholarship suggests the truth for a very few Edinburgh residents may be more nuanced.

Writing in the latest Journal of European Law and International Relations (1:4, pp. 21–63), St Andrews University academic Dr Anders Roligsak suggests the area roughly bounded by Pilrig Street, Leith Walk, York Place, Howe Street and Canonmills occupies a grey area within the European Union (Withdrawal ) Act 2018 and the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020.

Muddy waters

To understand Roligsak’s argument, one must consider Scotland’s troubled history during the mid-18th century.

What we now call Spurtleshire at that time remained a feudal barony, with power devolved by the King to Ker Bellenden, 4th Lord Bellenden of Broughton. A supporter of Charles Edward Stuart, he died in March 1753, the title passing to his son John Ker and descendants before vanishing into obscurity after 1805.

After painstaking research, Roligsak finds that, whilst the title may have continued down the generations, baronial authority had already shifted elsewhere. Bellenden was a sentimental supporter of the Jacobite cause during the 1745 rising, but also a political realist who recognised that the Young Pretender’s campaign was hopeless. Seeking to curry favour without drawing attention to himself, he retained the titular trappings of baronetcy but on 31 January 1746 sold (effectively sublet) the privileges of its essential tenantia sine titulo vel re to a third party.

Adventurer

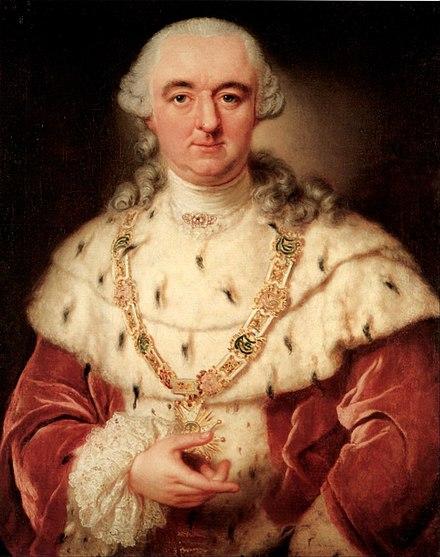

That party was the ‘German’ adventurer Harald von Garbsen (1690–1776), a speculator in cured-meats, spy, and agent provocateur who was loyal to King George II and in the secret employ of the Government in London. Von Garbsen left Edinburgh and returned to Hanover in June 1746, where he cleared gambling debts by selling his newly acquired Scottish rights to a representative of Karl Theodor, Bavarian Prince-Elector of the Holy Roman Empire (pictured below).

Theodore may have been Roman Catholic, but he was sufficiently benign and politically important in a troubled continent for King George to exercise royal prerogative by confirming this foreign princeling in his feudal accession in perpetuity. The measure was intended as a flattering if practically meaningless gesture. As such the barony’s legal status escaped Parliament’s 1747 Abolition of Heritable Jurisdictions Act which swept away most other such Scottish lordships held in baroneum.

In the decades which followed, Theodor never asserted his jurisdiction or contested the application of Scottish law on his domain. Perhaps for this reason, few remembered the barony’s continued reality. Sixty years later, it passed quietly into the hands of France when Napoleon Bonaparte established the Confederation of the Rhine in 1806.

Over subsequent long decades, this unrescinded anomaly of a semi-French enclave beside and later within the Scottish capital went unnoticed or was in no one’s interest to recall. That is, until Dr Roligsak chanced upon it in the archives of the Elysée Palace during researches into property-ownership provisions reformed by Brexit legislation two years ago.

So, what does all this mean for Broughton?

Roligsak provides 42 pages of dense legal argument and counter-argument before concluding that the situation is not clear-cut.

But in theory, he suggests that, given an agreed geographical definition of Broughton and a properly organised and supervised referendum, the old barony’s current electorate could choose to become part of a French administered microstate. Following that transition (and, for reasons too complicated to explain here, a dispensation from the Archbishop of Mainz), locals could next opt to merge with the département of Nord and welcome President Macron or his successor as their head of state.

With that, of course, would come reintegration into the European Union, and the problematic issue of customs barriers between Broughton and the rest of the country.

Good time to be a lawyer

Roligsak’s findings are controversial, and he himself concedes that Broughton’s accession to the EU faces tremendous hurdles. But, with sufficient public support and funding for a campaign, the issues could potentially exercise the minds of constitutional lawyers for many years to come.–AM

Got a view? Tell us at spurtle@hotmail.co.uk and @theSpurtle