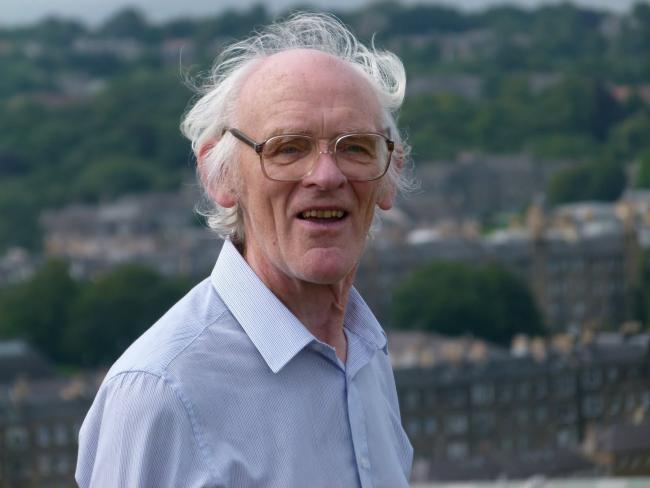

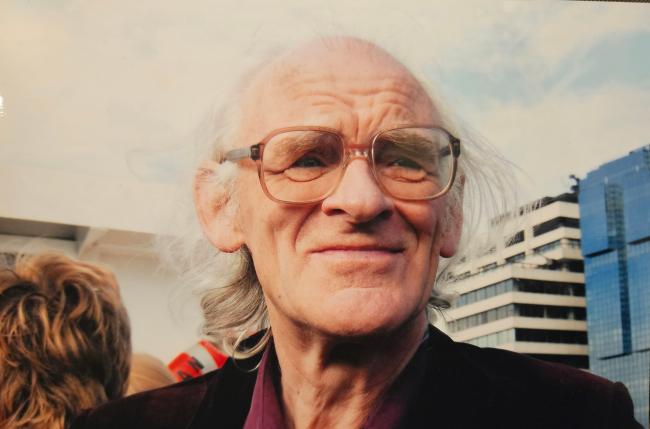

John Dickie, founding editor of the Broughton Spurtle, died on 28 December 2024, aged 83. His funeral took place at Warriston Crematorium on 20 January. Below we publish a slightly extended version of the eulogy delivered on that occasion, written jointly by his sons Mure, John and Andrew Dickie.

*****

If you had been on the coastal road onArran just before dawn on a summer morning in 2005 you might have seen a lone figure striding out of the darkness between the hills and the sea. That man, by then well into a sponsored, solo 24-hour walk around the whole island, was our father, John Wallace Bowe Dickie; husband to Eileen, father-in-law to Yuka, Leslie and Kirsten; Granda to Mhairi, Naomi, Andrew, Matthew and Kiva; brother to Michael, Catherine, Elspeth and Donald; uncle to John, Alisoun, Mure, Elspeth, Jane and Mary Kate, and friend to so many of you here today or watching online.

Dad was a man of many parts: a community campaigner; an activist dedicated to change both global and local; an educator, a history researcher; a writer and editor, and above all, for us at least, a loving family man.

Early years

The son of Dorothy and Mure Dickie, he was born – to the intense excitement of his elder siblings – on 13 June 1941 at ‘Glencloy’, a semi-detached house on a quiet street in the east coast town of Carnoustie. The family later moved to Dovecot Road in Corstorphine, where Dad showed the first signs of his more rebellious streak. He enjoyed throwing crab apples at neighbours’ doors and windows, prompting one to threaten to take him to Torphichen Street police station. His younger brother Donald recalls Dad sending one snowball sailing through the open window of a passing lorry, whose furious driver took his complaint to an even higher authority – their mum.

And when Michael, Dad’s elder brother by 13 years, tried to tell Dad and Donald off for rampaging around the garden when he was trying to study, they would just tell him: ‘You’re not our father!’

Later there were some wild parties when the parents were away and an unapproved – and unlicensed – attempt to drive his father’s new car to Queensferry so a friend could visit a girl in Fife. He was involved in an incident where local street signs turned up in his school’s gym. But it was also at school where Dad first showed his journalistic inclinations, editing the school magazine in his final year. The editorial in the Melville College Chronicle’s December 1958 edition reflects one of Dad’s lifelong enthusiasms when it mentions ‘Louis Armstrong’s supremacy’ among jazz fans. Dad’s friend Tom Lee remembers being encouraged to join the Corstorphine Youth Fellowship on the basis that it was a good excuse to get out on a Sunday evening and allowed access to a jukebox. Louis Armstrong would later be joined in Dad’s musical pantheon by Bob Marley, whose work he got to know well in 1986 through an Open University course on Third World studies.

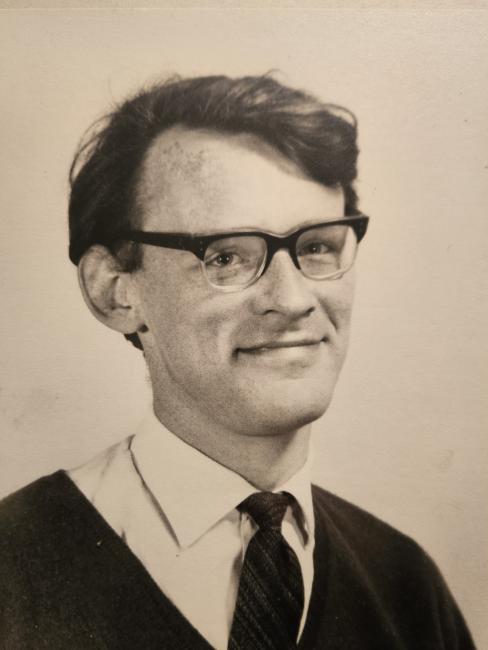

At Edinburgh University, Dad studied History and in 1960 made the first of many appearances in The Evening News as part of a group of students who lived for a week in a hut in Princes St Gardens on a shilling a day, raising awareness of the plight of refugees. After graduating in 1963, he joined the Voluntary Service Overseas charity to teach history at a secondary school in Nyasaland and he was there in July 1964 when the British territory was reborn as the independent nation of Malawi. After two years in Malawi, it was on the boat back to Britain that he met a certain young lady named Eileen Keohane.

Eileen Keohane

That meeting has become a family legend. Mum recalls spotting a nice and friendly-looking man on a lower deck a few days into the voyage, but being quickly dismayed to see three children rush over and begin crawling all over him – so that when Dad happened to look up and see her for the first time she hardly had her most winsome expression in place. Fortunately, they soon realised their mistakes: Dad was not married but just playing about with the children of a family he often babysat for – and Mum did not always go around with a face ‘that would curdle milk’.

Fortuitously, Dad was enrolled to study community development at Manchester University, very near where Mum’s parents lived in Sale. But Dad took a while to pop the question. In early 1967, Mum connived her way to get a seat next to Dad’s on a plane that stopped in Kampala, Uganda where she was then teaching. This seems to have been a complete surprise to Dad, but as they crossed the Equator, miles up in the sky, he asked her to marry him.

Their wedding in Manchester in December 1967 brought together a Scot of solid Protestant stock with an Irish Catholic, but Dad was a very tolerant non-believer who was happy to agree to his children being brought up as Catholics. An easy-going priest was found in Manchester, and he and Dad used the time allotted for the compulsory pre-wedding religious education to discuss and drink whisky instead. Mum and Dad would go on to become a formidable team, close partners in his most important projects and presenting an ever-unified front when it came to bringing up the three of us.

Back in Malawi, Dad worked at Magomero Community Development Training Centre, helping prepare Malawians for roles previously controlled by the colonial government; or, as Mum puts it, teaching people to do him out of a job. They both loved Africa, but after John and I arrived, worries about schooling for expatriate children (neither of them liked the idea of sending us to boarding school) prompted a move to Edinburgh.

Back in Edinburgh

After sojourns on the South Side and Comely Bank, they settled in a basement in Great King Street and, joined by Andrew a few years later, became permanent residents of what would later become known to many as ‘Greater Spurtleshire’.

In 1972, Dad was appointed as the first Community Relations Officer of the new Lothian Community Relations Council (CRC), soon establishing it in a permanent office on Forth Street. His first main task was helping refugee Ugandan Asian families settle in Scotland, and many of them got an early introduction to a full cooked Scottish breakfast at the Great King Street flat, where Mum’s very basic Swahili was put to good use.

Dad believed passionately in the need to attack racism, promote equal opportunity and ensure that schools and other institutions reflected the multicultural nature of our society. Then as now, there was resistance. After the CRC published a short guide for medical staff about the beliefs and customs of minority groups, Dad got a letter from a Perthshire doctor – on headed Tayside NHS notepaper – denouncing this ‘monstrous' and 'misguided' effort to force compliance with the ‘various demands of people who are not naturally of this country’. We have come a long way since then, but Dad always felt there was much still to do.

Unlikely employment

In 1979 and 1980, he retrained as a primary school teacher, but a suitable permanent position proved hard to come by and in 1985 he took a job instead as a guide at the Palace of Holyrood House. It was not an obvious role for a lifelong republican who printed his own stickers to denounce royal greed and privilege during the late Queen’s 40th jubilee and marked Charles’s recent coronation by directing Mure to put up anti-monarchy posters in the garden. But Dad loved doing his own research into the Palace’s rich history and then sharing it with visitors. His bosses, however, were not so pleased when he went off script, and at least one American tourist complained to the authorities that he had been a bit dismissive about the current royal family. Andrew remembers being allowed to sit on the Queen’s throne during a private tour. In an even greater act of lèse-majesté, Andrew’s pet rats ate holes in Dad’s official-issue royal tartan trews, forcing Mum to labour late into the night, darning them for the next day’ s guiding.

Around this time, Dad got a seasonal job as a Santa at the Goldbergs department store which used to stand at Tollcross. Some might have questioned his physical fitness for the role – Dad hardly had the classic rounded Father Christmas figure – but his easy way with children made him a perfect fit. It was a special pleasure for us boys to get to go and see our own Father Christmas at work. One day, another little kid visiting the grotto grabbed a couple of the golden balls decorating the Goldbergs Christmas Tree, prompting his mother to say loudly: ‘No, no, give Santa back his balls.’ Happily, Santa’s balls were returned and even came home with him. His balls have hung proudly on the Dickie Christmas tree ever since.

In the last chapter of his working life, Dad joined with Mum to jointly run the guesthouse at 22 East Claremont St, where they had moved in 1983. It was, as a neighbour recalls, the only B&B on the street that had political campaign posters in the windows, but there was a warm welcome for anyone at the door. It was a thriving business when Mum and Dad retired in 1998 and moved to Hopetoun Crescent.

Activism, history and active retirement

Retirement was less of a change for Dad than for many people, because paid employment was only ever part of his life’s work. In the 1970s, he was highly active in anti-nuclear campaigns and the Scottish National Party, organising fundraising jumble sales in Rodney Street, taking us kids on marches and joining the SNP’s influential left-wing 79 Group. While his focus later shifted away from party politics, his support for independence never wavered – as anyone who passed the garden in Hopetoun Crescent during the 2014 referendum could testify.

For decades, he campaigned keenly against fascism and apartheid, for fair trade, global justice and gay rights, and in support of striking workers. He was deeply committed to peaceful action, but was no pacifist. Mure remembers him raising his fists in almost Victorian fashion to fend off rowdy elements disrupting a march he was stewarding. John recalls him having his glasses knocked off while trying to calm a crowd at an anti-fascist demo after the punk band the Clash failed to turn up. And he himself confessed to having once kneed a policeman in the balls, but only to protect another protestor on a Dundee Timex picket line.

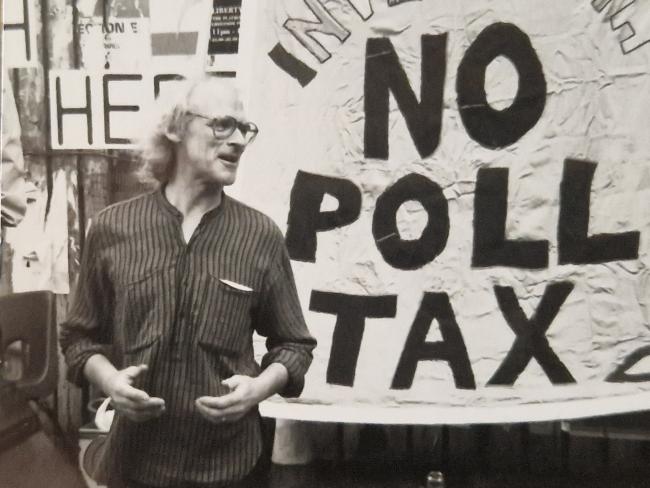

Dad was a leading figure in local resistance to Margaret Thatcher’s poll tax. He and Mum hosted meetings of the Broughton/Inverleith Anti-Poll Tax Group in their front room and championed refusal to pay, holding out themselves until Council legal action threatened to kill their B&B business. Andrew, then a teenager, was deployed to watch out for the police when Dad led guerrilla anti-poll tax fly-posting missions around the neighbourhood. For Dad, the power of such grassroots politics was demonstrated when the government abandoned the tax, admitting it had become 'uncollectable’ .

The next big local campaign, to save London Street Primary School from closure, did not have such a happy ending. But Dad was convinced of the value of uniting local people, of widely different backgrounds and classes, in shared political endeavour. Even a lost cause could empower communities. Bringing ordinary people together would invigorate our democracy.

It was in this spirit that he published Cause to be Proud, a book of interviews with members of the local anti-poll tax campaign. Ian Bell of the Herald wrote that it amounted to ‘the war memoirs of the people in Edinburgh’s Broughton/Inverleith who have come through the community charge still fighting, still believing that the monolith of central government can be opposed and beaten’. In 1996, Dad published Save Our School, a collection of interviews looking at the lessons of the London Street campaign. Both books embodied his approach, offering a broad range of experiences and opinions produced with scrupulous care for editorial accuracy and fairness.

The books were also exercises in instant oral history, but Dad retained his interest in the more distant past. In 1996, he founded the Broughton History Society, which has hugely enriched understanding of the development of the former barony and is still going strong today. For many years he also edited the society magazine.

Founding the Spurtle

One of Dad’s proudest legacies was his role as founding Editor of the Broughton Spurtle, a hyperlocal newspaper launched in February 1994 by a small band of fellow residents inspired by the poll tax and school campaigns to bring together people who wanted to change the area for the better and, as its manifesto declared, ‘generally stir things up a bit!’ Determinedly independent of any political group or party or other interests, the Spurtle has become a part of the fabric of the city and a beacon for other communities worried by fraying social ties and the collapse of quality local journalism.

Current Spurtle Editor Alan McIntosh, who has helped steer the monthly to ever greater success, says Dad ‘gave local people confidence to respect their own opinions and articulate them in pragmatic terms’ and ‘set an editorial tone that could be courageous and controversial but remained calm, courteous, reasoned, enabling, informative and collaborative rather than confrontational’.

It was an approach, as Alan says, that has many lessons for political discourse today.

Family man

For all Dad’s varied passions, we boys always felt loved and included. It was clear to us that his family, Mum and all of us, were the most important things in his life. Family holidays in Arran, Skye or Torridon were joys despite the chilly bathrooms, clouds of midges and horizontal rain. John’s earliest memory of Dad is being on a walk with him in Malawi and seeing a snake; their last conversation was about walking the West Highland Way in 1981. Mure treasured cycling trips alone with him in the Borders. And Dad happily indulged all our interests: he took Andrew to a role-playing convention in Bradford and accompanied him through a marathon back-to-back screening of all three original Star Wars films in 1983.

We know from the messages we have had in the last few weeks that Dad was an inspiration to many people. He had a way of sending people down interesting roads. His niece Elspeth credits him with fostering her life-long fascination with drumming, helped by the gift of an African drum, that led indirectly to her meeting the father of her son Alhadji. Elspeth’s sister Jane credits Dad’s long dedication to helping make the global trading system more just (a cause that subjected us to a lot of rather bitter Nicaraguan instant coffee) for inspiring her to volunteer at the One World Shop in Edinburgh where she met her husband and the father of her four children.

Dad was certainly a huge inspiration to us, especially in our efforts to be good Dads and partners ourselves. You will have to ask our own families how well we are doing.

The pride and pleasure Dad took in parenthood was matched by his delight in and love for his five grandchildren. Until the end he relished telling stories of his youthful naughtiness to Kiva, sharing funny jokes with Naomi, or discussing their lovely hand-drawn birthday cards. He loved recalling Andrew's enthusiasm for childhood outings around Edinburgh and the Lothians with him and Mum, where they shared their love of places and history. And Dad’s mood would always be lightened by a visit from Mhairi or Matthew.

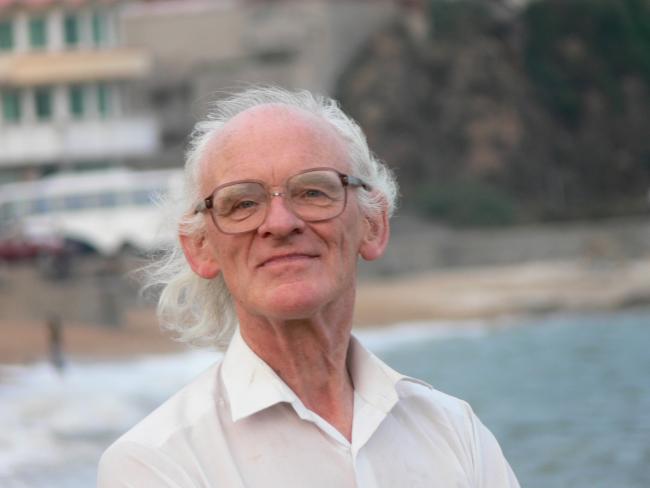

Dad’s last decade was increasingly tough for him. He still enjoyed meeting up with his friend Gavin in the Botanic Gardens and trips with Donald to see Michael in Ayr and going to see films at McDonald Road Library with Mum. But he was troubled by even minor failures of memory or clarity of thought. Becoming less mobile was a particularly heavy blow, for Dad had always loved to walk. That epic unsupported circumnavigation of Arran – during which Dad even declined on principle an offer from a friend he bumped into to pause for refreshments – was only one of a number of long solo challenges. At the age of 69 he walked alone to the Falkirk Wheel and back, a distance of 66 miles.

Fiery vital sparks

But even when bedridden in his final weeks, Dad always knew who he was and who we were, and could still take clear pleasure in his family. Speech became difficult at the very end, but he could still, as Mum put it, laugh with his eyes.

Dad’s mother Dorothy, or Dorrie – who we knew as ‘Naki’ – was a keen poet, and in 1989 he collected some of her poems in a wee booklet. One of them describes how a person might hold on to their youthful passion, continuing to scatter their ‘fiery vital sparks’ as they fight their favoured causes even in old age.

At the last hour of such a man, Naki wrote, the tree of his life would seem to be ‘...twisted, tangled, gnarled of root’, but also 'Bowed rich and glowing with its careless fruit’.

In the last few days we found in Dad’s desk a letter from Naki in which she told him how much joy he had brought her, and thanked him for giving her 'such a dear daughter-in-law’ and for the 'intense happiness’ of three more grandchildren. We are sure Naki would have been even happier if she had known just how fruitful the tree of Dad’s life would become.