EDINBURGH’S FLAWED TRAMWAY … AND HOW TO FIX IT

Dave Holladay is a highly experienced transport and engineering professional with first-hand knowledge of tram and cycling-related issues (see Profile).

Over recent years, he has monitored defects that became apparent during Phase-1 construction of Edinburgh’s tram track (Airport–York Place) and its subsequent deterioration since coming into use.

Below, Holladay outlines concerns and suggests remedies in advance of Phase 2 starting this autumn. He continues with an ambitious proposal of his own for how to deliver optimum connections to the rest of the city, and concludes with a brief note on falling off bicycles and ways to avoid doing so.

Something rotten

The images below show just some of many examples of the continuing movement and cracking of track slab between Haymarket and North St Andrew Street.

Notable are:

- How tarmac and concrete have cracked, moved, and bits have fallen out along with the poured rubber seals at construction joints, and around the rails.

Loose repair uncoloured concrete – movement between slabs (2 cracks) – camages and patched seals

Crack at joint between slabs with concrete lumps held in place on steel reinforcement bars – tarmac seal failed and split from edge of concrete patching on poured seals.

The Mound/Princes Street junction – seal pulled out.

- The use of ‘temporary’ steel road plates (anathema to cyclists), which in some cases have been in place two years, or longer.

- The continuing and often substantial settlement of carriageway running beside the concrete track slab and the chamber covers and frames. This looseness causes clattering under the hammer blow of every passing bus, and requires frequent repair.

Manhole cover, Shandwick Place – notice traces of several repairs (neatly cut out damaged tarmac and replaced with new)

- At many locations you can see two cracks, around 25cm apart, where the load-transfer reinforcement bars are cast in between each section of the upper slab. As this damage progresses, lumps of concrete detach and get carried away by passing traffic. A variey of repairs have been made with concrete and tarmac. Concrete still attached to the reinforcement bars is left bouncing around as vehicles cross, and will even move when a person stamps on them. Patch repairs in a variety of materials have been made, but the slabs continue to break up and carriageways continue to settle.

Concrete falling out.

Ground strength

It is notable that the original Manchester Metrolink street track also suffered from movement, and for the second city crossing there was a contractual requirement to have a ground strength test (to achieve a California Bearing Ratio [CBR] of 15%) before any track slab was laid, with provision for remediation work if necessary before any concrete was poured.

Edinburgh’s tram tracks run over some pretty lousy ground – wet alluvial deposits over fractured shale – which caused problems when the railway tunnel was built under Scotland Street in the 19th century.

But the situation seems to have been worsened when 200-years’ compaction and stabilisation (thanks to the undisturbed original streets from Haymarket eastwards) were removed during tramwork excavation, and perhaps not sufficiently consolidated before the road and track went down on top.

The settlement of the tarmac carriageway and cracked concrete suggest that the supporting ground may not be ‘strong’ enough to spread and carry the loads imposed. A prudent response would be to promptly carry out CBR testing by coring a small hole (from c.50mm) to do the load testing, and a vane test (soil cohesion) can also use a relatively small hole to insert the test probe.

This section of Princes Street has sunk around 15cm (height of kerb). Tarmac has been thrown into the sunken part (not a careful prepartion and repair patch), with a road plate covering a further hole, and sinking mahole frame further out from the kerb.

Just as well the bus driver went wide and slow.

Below standard

The transverse profile of an embedded tram rail is a critical detail, particularly for two-wheeled road users, but also for car drivers, as the Roe vs Sheffield Supertram & Ors civil actions have highlighted. But extreme divergence from the standards advised by the government’s Office of Road and Rail (ORR) typifies the pitiful quality of Edinburgh’s Phase-1 track.

Edinburgh track, as new (5p piece = 18mm) - showing ridge 10mm high between concrete and poured joint filler. (This filler requires regular repair where bus tyres rip it out from between rail ad concrete plus joints in concrete and concrete-tarmac.)

ORR standards were achieved for Phase 1 of the Nottingham Express Transit in 2004, and are still in very good order after 14 years. They were also successfully delivered by the joint venture team on all the recent Manchester Metrolink works, and in work on the Blackpool Tramway upgrade with the link to the North railway station due for completion in 2020.

Edinburgh, however, failed to meet these standards, and, as a result, has ended up with a ploughed field of multiple grooves and upstands, mostly exceeding the 3mm (steel/low-friction) that are established and tested limits for raised edges of street ironwork, thermoplastic markings, or 6mm (concrete/high-friction) for dropped kerbs, paving slabs (trip hazard), level-crossing panels, etc.

The 6mm (0.25”) standard for tram rails, (+3mm to -3mm above/below road surface) – which has existed since the 1870 Tramways Act – was delivered in Manchester using a well-rehearsed finishing regime. Here, they’re delivering a consistent +2mm for the road surface (concrete, with high-friction roadstone content) above the railhead.

Manchester – new track as delivered for second city crossing

Edinburgh, on the other hand, delivered a new installation with a 10mm ridge where the rubber embedding abuts the rail. This has created two extra grooves for the bike tyres to cross, plus the ridge/slot where the tarmac can split from the concrete at the edge of the top slab.

To cut a long story short, I believe the contract and standards for construction of the forthcoming Edinburgh tram extension can and should match those seen in Manchester and Nottingham, as a minimum.

Improved plan for Edinburgh trams

Serious consideration should be given to re-thinking the tramway’s central core, ideally putting this under Princes Street – possibly all the way from Haymarket.

The south ‘wall’ of such a tram ‘tunnel’ would be a colonnade, providing an under-cover view of the Gardens and Castle, for events. The north side would offer an all-weather shopping arcade with access to the basement levels of Princes Street business premises.

Such a layout would also allow trams to keep running, at an increased frequency if required, when a major event closes Princes Street, thus delivering a high-capacity transport service for crowds entering and exiting the city centre.

This arrangement would prepare for below-street junctions at Lothian Road and North Bridge, and resolve the currently planned mess of junction arrangements at Picardy Place. It would provide tram stops where they are logically needed at Lothian Road and Waverley Station. Improved underground connections could link Waverley Station, the St Andrew Square bus station, and the new Edinburgh St James.

At the future junctions and at Leith Street, the tram tracks could then emerge in the middle of the carriageway and for the route to Leith the trams could travel the whole way down the centre of Leith Walk.

Conclusion

In Brussels, trams run on a reserved track in the centre of the street, and thus use level crossings, with veloSTRAIL where appropriate. A similar designed-in detail – with grass-track for cooling, drainage management, and carbon capture – could be part of any future tram plans in Edinburgh.

Manchester and Nottingham have lower incidence of crashes, and far better quality of finish for their on-street track. Their knowledge and experience need to be brought into delivery of new tracks for Edinburgh, and if the core section of Edinburgh’s system is going to be Princes Street, with increasing frequency of trams as each route opens, then a fully segregated central section – grade-separated at major junctions – must be a long-term consideration.

A brief note on falling off and how to avoid it

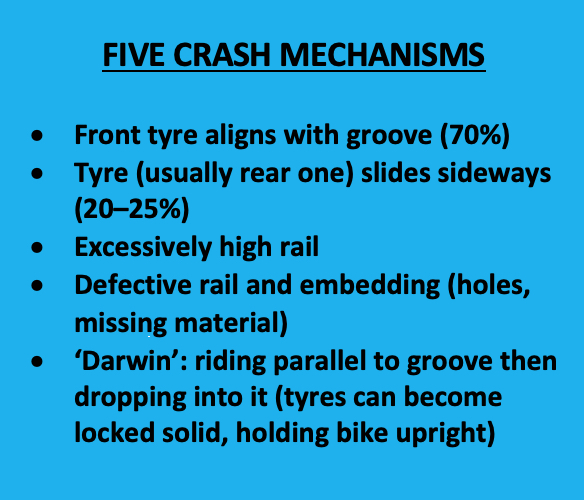

As research from Edinburgh and Toronto highlights, most cyclists fall at tram lines because the actions of another road user ‘distract’ them as they cross. Some 70% fall because of just one ‘mechanism’, with a further 20–25% falling due to a second one.

In total, five distinct mechanisms (reasons for falls) have been identified – see panel below.

37mm bicycle tyre is perfect fit for a track groove.

The two main reasons for falls could be mitigated by replacing one of the two smooth edges that the cycle-tyre contact patch sits on with a high-friction surface. This author has done some initial work on this, and hopes to find funding and support for further research. He’s interested in testing this in concept form on a ‘dead’ section – e.g. the end of the current line at York Place.

In the meantime, here are ways to deal with the two main causes for cyclist falls.

- To avoid the front wheel turning into the groove and jamming, avoid crossing too slowly.

- Apply firm but not rigid control of the handlebars – the forward momentum should overcome the forces trying to turn the tyre, and a firm hold on the steering will stop the tyre turning.

- To avoid sliding sideways (which can happen at all crossing angles), avoid turning or braking as you cross the rails.

- The Edinburgh and Toronto studies confirm that having a driver on your tail, or needing to slow down or turn to avoid a collision, will increase the likelihood of skidding and crashing on tram rails as you cross them. Try to keep a safe distance from vehicles behind, and pay close attention to the situation you are approaching.

Got a view? Tell us at spurtle@hotmail.co.uk and @theSpurtle

---------------