From the Edinburgh Evening News, 19 January 1904.

SIR HERBERT MAXWELL'S ADVICE ON READING.

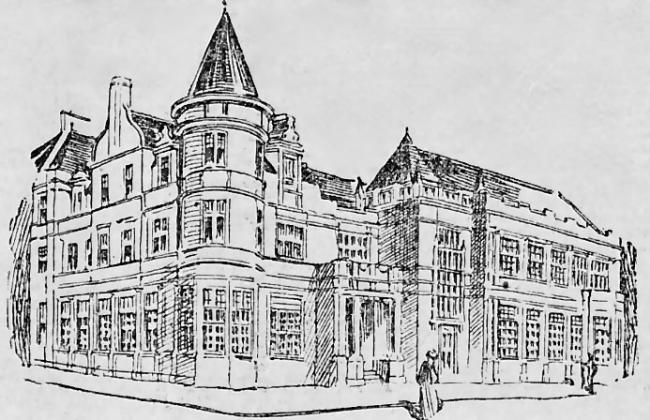

The new East branch of the Edinburgh Public Library, situated at the corner of M'Donald Road and Leith Walk, was opened last night, when Sir Herbert Maxwell delivered an address to a large gathering in the reading-room.

Mr G. M. Brown, M.P., was in the chair, and after prayer the Rev. Lamond, Greenside Parish Church, stated that this was the third Nelson Hall and Branch Library erected under the bequest of the late Thomas Nelson. The success of the other two halls, in Fountainbridge and Stockbridge, had proved that Mr Nelson's bequest was a most useful one. (Applause.)

A large number of citizens had taken advantage of them for the purposes of pleasant intercourse and healthy amusement and profitable reading. The success these halls had also been largely due to the association of the branch libraries with them, and on behalf of the trustees he heartily thanked the Library Committee and Mr Hew Morrison, the chief librarian, for their co-operation. (Applause.)

He feared this would be the last hall that could be erected under the bequest in the meantime. The original bequest, he explained, amounted to £50,000, and, in addition, interest had accrued, raising the total at the disposal of the trust to £61,000. Out of that there had been spent on the Fountainbridge Hall £7700, on the Stockbridge Hall £8200, and on the new building now being opened about £12,000. (Applause.) These amounted together to £23,000, leaving a balance of £33,000.

For the upkeep of the halls, the trustees were in possession of about £1000 in interest, besides £450 they received in rents from the Library Committee—a total income of £1450, which was just a little more than was necessary to keep up the three halls and pay feu-duties and expenses that might arise. For the upkeep of Fountainbridge and Stockbridge Halls, £900 was required, leaving £550 for the upkeep of the new hall.

There was, therefore, little chance of the trustees at the present time being able to proceed with the erection of another hall. In conclusion, he alluded to the introduction of a gymnasium as a new feature of the hall. He thought that was an excellent addition to the building. (Applause.)

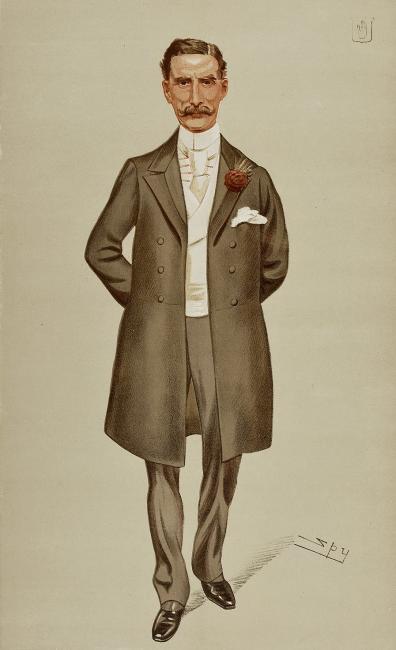

Sir Herbert Maxwell [pictured below], in declaring the buildings open, said there was scarcely anything more full of hope for the country than the object which had brought them together. What struck him as a peculiar characteristic of the present age was the amount of thought that was given by those who cared for the welfare of their fellow men to the nature and kind of recreation that was brought within their reach. Of those persons was the late Mr Thomas Nelson. (Applause.) At each of the two halls already opened, ten thousand volumes were circulated per month. Upwards of 760,000 volumes were circulated last year from the Central Library, and considering the population of the city the amount of activity thus shown in a literary way was exceedingly interesting and gratifying. (Applause.)

A DEFENCE OF FICTION.

Some people said, "Oh, there are plenty of readers, but what they read is novels; they don't read improving literature." Well, that did not seem to him to be a discouraging feature. (Applause.) He protested against the estimation too readily made by some moralists that all light reading was deleterious. (Applause.) He could quote a whole row of authorities of the contrary view. Illustrating his point that there was a large number of persons with abundant leisure and means who hardly ever opened a serious book, he instanced the case of a man who had received a most expensive education, and who on setting out on a long railway journey with him purchased at the bookstall the "Sporting Times," "Tit-Bits," "Ally Sloper's Half-Holiday," and a daily paper. (Laughter.) He did not mean that there was any harm in these journals, but it was rather humiliating to find that he had no higher aim than that exceedingly ephemeral literature. (Applause.)

Sir Herbert said he would not draw any gloomy conclusions if the returns of the library showed that novels were more in favour than the more serious books. The proportion of fiction circulated from the public libraries in Edinburgh was smaller in percentage than in any other great town that he was acquainted with; it amounted to 60.77 per cent., or three-fifths of the whole.*

When they heard people talking slightingly of fiction, they should think of the amount of good that had been done by fiction. The Founder of Christianity himself spoke in parables, which might have had some foundation in fact, but which were in the form of short stories, a form of fiction. If they read fiction they could not read more than one-tenth part of what was published. Let that be the best tenth.

They should choose books that held up a high ideal of human nature, stories of pure love and clean living, lofty aims and willing sacrifice, and sometimes he thought they would find it advantageous and more amusing than they might think to turn from the works to the lives of the writers themselves. Scott's life was a great romance; yet for every hundred that read his novels only one read his life by Lockhart.

A DEEP DEBT OF GRATITUDE.

Mr John Harrison, convener of the Library Committee, acknowledged the deep debt of gratitude the city owed to the Nelson Trustees, who came to the rescue of the committee when it was found that branch libraries were required for the districts of the city. It was a noteworthy fact that before the establishment of the branches the circulation of the volumes from the Central Library was falling off. In 1891, the first, year, there were 748,000 volumes circulated; in the year before the first branch was opened, the number had fallen to 456,000, so that the need for branch libraries was proved absolutely. (Applause.) He moved a vote of thanks to Sir Herbert Maxwell, and Mr T. A. Nelson, a son of Mr Thomas Nelson, seconded' and asked Sir Herbert's acceptance of two sets of books—the works of Thackeray and Scott—in lieu of the customary key. (Applause.) Sir Herbert, in acknowledging the gift, said it could not possibly have taken a more acceptable form.

The chairman then congratulated the architect, Mr Ramsay Taylor,** on the planning and equipment of the building, and Baillie Michael brought the proceedings to a close by proposing a vote of thanks to the chairman. East Edinburgh, he remarked, had waited long, and not always patiently, for a branch library, but he now felt that the delay had been all to their advantage, for they could claim to have the largest and best equipped institution of the kind in the city, if not in Scotland. (Applause.)

He believed that the opening of the Nelson recreation halls and reading rooms, not necessarily conceived on that grand scale but perhaps on a smaller scale, in every populous district of the city, would do more to rear up in our midst a sober and self-respecting generation of citizens than would the shutting of half the public-houses in Edinburgh, for whereas the most certain result of the latter would be to play into the hands and pockets of the other half that remained, the benefits of an Institution of this kind would simply be incalculable. (Applause.)

The library was opened to the public this morning at nine o'clock.

* Maxwell's prediction of reading tastes was later borne out by figures for the week ending 10 December 1904. From its stock of 11,896 books, the number issued to the public from East Branch were broken down by genre as follows: Theology 39; Philosophy 12; Sociology 52; Science and Art 147; Poetry and Drama 43; Fiction 2,332; History, Biography, Travel 174; General Literature 207; Juvenile Books 1,115. The grand total (4,121) is below the weekly average of today's McDonald Road Library: c.5,600.

** See the Dictionary of Scottish Architects. Search for Taylor, Harry Ramsay here.