Unreliable Geographies by Aeneas McHaar

No. 12: Claremont House, Esher, Surrey, England

51º 21’ N, 22’ W

Claremont Crescent appears in an 1821 map of Edinburgh by Knox, two years before building work began. It was the first part of Broughton to be so called, and the latest example in a time-honoured, New Town tradition of brown-nosing the Royal Family. Royal forenames, titles, origins and in this case property were all plundered in search of suitably up-market, politically correct designations for smart developments.

Claremont House (near Esher in Surrey) began as a ‘very small box’ built by the architect and playwright Sir John Vanbrugh in 1708. (Vanbrugh’s more famous designs included the baroque Castle Howard, setting for a 1981 TV adaptation of Brideshead Revisited: a baroque box within a box.)

U and non-U

In 1714 he sold the property to a Whig toff, Thomas Pelham-Holles (Earl of Clare, twice future PM, and Duke of Newcastle), who commissioned Vanbrugh to slap on a couple of wings at either end. This improved design Clare called Claremount, downplaying the House. Next, the u was dropped as its pretentious occupants basked in the bogus but more French and sophisticated-sounding ‘Claremont’.

Robert Clive – a fabulously corrupt and wealthy nabob who helped found Britain’s first foothold in India – bought Claremont from Newcastle’s widow in 1768. He sensitively demolished it, then had a new, Palladian mansion knocked up by ‘Capability’ Brown and friends on an adjacent but less damp site. His marble plunge-bath survives. The house was finished in 1774, the year after Clive’s suicide.

In bed with royalty

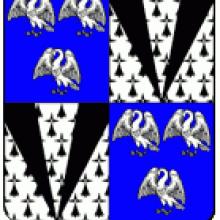

In 1816, Claremont changed hands again, this time for £69,000. The state Commissioners of Woods and Forests presented it as a first step on the property ladder to newly weds Charlotte and Leopold. Princess Charlotte was the daughter of the future King George IV. Leopold was a charming but cash-strapped princeling from the backwoods of Thuringia (a popular destination for visiting armies) who, as a soldier and diplomat, had eventually done rather well out of the war against Napoleon.

Aware that small was not beautiful in the chien-eat-hund power struggles of Continental politics, Leopold saw the marriage partly as a strategic alliance which would protect his dynasty. (One soon realises Leopold was good at knots.) It would also please his bank manager, since Charlotte brought to the nuptial bed a £60,000 dowry and yearly income to match, both voted by Parliament.

Tragedy

The couple apparently had a tempestuous but loving relationship in among the banknotes, but it ended at Claremont all too soon. Following months of bleeding and malnourishment prescribed by doctors, Charlotte endured a 50-hour labour then died shortly after giving birth to a stillborn child in 1817.

Compared to the scandalous excesses of her parents and uncles, the conventional morality of Charlotte and her ‘modest’ domestic arrangements with Leopold had boded well for the House of Hanover. (Charlotte was the only legitimate heir at the time.) Her passing – tragic, unexpected, politically unsettling – was met with outpourings of grief. ‘The sensation excited throughout the country by this melancholy event was of no ordinary description,’ remembered the Chambers Book of Days 52 years later, ‘and even at the present day it is still vividly remembered. It was indeed a most unexpected blow, the shining virtues, as well as the youth and beauty of the deceased, exciting an amount of affectionate commiseration, such as probably had never before attended the death of any royal personage in England.’ Details may have changed, but that intoxicating mix – feminine youth; glamour; unpopular senior royals; and death – rings bells.

Onward and upward

Leopold remained in Claremont after his bereavement, partially consoling himself by acquiring various commons nearby, creating a beautiful sylvan environment there, then shooting anything with a beak which strayed into it. Still popular throughout Britain, he was awarded the Freedom of Edinburgh in August 1819, and for him Edinburgh’s Claremont Place, Saxe-Coburg Place, Claremont Park, Leopold Place and Coburg St were also named in the 1820s.

In 1831, Leopold was invited to become King of the Belgians and – as I’m sure most of us would so long as there was a reliable ferry connection to Rosyth – accepted. The next year he married Louise Marie of Orléans (a raunchy Bourbon blue-blood), by whom he had 4 children, one of whom they named Charlotte.

Ever the diplomat, he arranged for his sister, Princess Viktoria, to marry Edward, Duke of Kent (one of George IV’s younger brothers). In 1819 that happy couple produced Victoria, who would go on to have a lifelong affection for Claremont which she had visited in childhood. This future Queen-Empress – thanks to Leopold’s manipulations – was hitched in 1840 to Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, the younger son of Leopold's older brother Duke Ernst. (Twice round the tree and back down the hole.)

All this while Leopold retained Claremont. In the years to come, the vacant house proved a convenient place of exile for various down-on-their-luck French in-laws. Louis Phillippe – Louise Marie’s dad and last king of France, who abdicated in 1848 – settled at Claremont with his family and died there in 1850. His widow survived him on the premises until 1866.

Set for success

Following Leopold’s own death in 1865, Claremont was eventually reacquired by the Crown Estate and remained in royal hands until 1920. The Crown still owns the woods, but the National Trust manages its 50 acres of landscaped gardens. In Louis Gilbert’s 1956 film Reach for the Sky, Kenneth More as Douglas Bader appears on the lawns outside Claremont House with other recovering airmen. More recently, scenes in Meridian Television's Hornblower series were shot here.

Claremont House is now the Claremont Fan Court School, a co-educational establishment dedicated to developing ‘confident, happy and responsible’ young people whose parents can afford at least £13,000 per year for the privilege. A different Claremont House is one of two administrative units at Drummond Community High School, where confident, happy and responsible young locals attend free.

From now on Mr McHaar's 'Parallel Broughtons' will appear here in Breaking news. However, his previous eleven unreliable geographies will continue to gather cyber dust in Extras:

2. Rodney Street, Helena, Montana, USA

3. Broughton Island, New South Wales, Australia

4. Beaverbank, Nova Scotia, Canada

5. Lower Broughton, Salford, England

6. Bellevue d'Illlinini, French Guiana

7. Blandfield, Essex Co., Virginia, USA

8. Gayfield Park, Arbroath, Scotland

9: Dunedin Streets, Otago Province, New Zealand