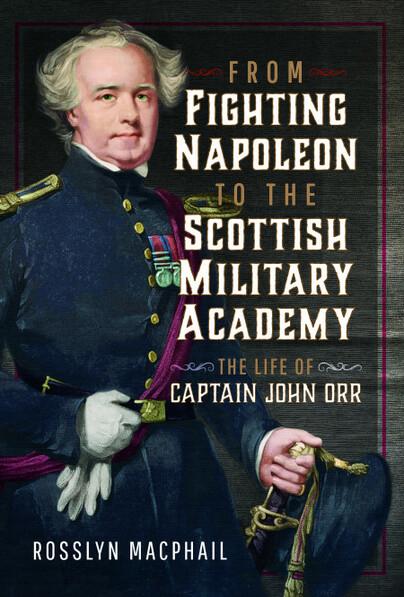

Local author Rosslyn MacPhail’s biography of her great great grandfather Captain John Orr (1789–1879) was published in October and will be launched later this month in Edinburgh Castle.

Based on a previously unseen campaign diary and letters, From Fighting Napoleon to the Scottish Military Academy recounts Orr’s active army career in the Peninsular campaign from 1811 to 1814 (Salamanca, Burgos and the Pyrenees) and then at Quatre Bras and Waterloo (1815), where he was wounded in the knee and later pensioned off.

Orphaned in childhood, Orr likely volunteered first for the Stirling then Edinburgh Militia before joining the 42nd Regiment. His time in Portugal and Spain is told through a diary which he kept after arrival in Lisbon in 1812. This is interesting in its detail of a young officer’s personal clothing and kit, but in general is a rather stoic account more concerned with places than people.

Nevertheless, there are understated and harrowing details of the privations and vicissitudes experienced by long-suffering British foot soldiers. These included: fever and dysentery; appalling rain, heat and cold; 18-hour marches, lice up to the knees ‘thick like dust’.

Although promoted on merit to a lieutenancy in 1813, Orr did not enjoy a private fortune, and his meagre wage was insufficient to buy his way out of hardship. Like other kilted soldiers in the campaign, he was no stranger to the horrors of ticks and fleas in places no-one would want them.

There were, of course, other things to worry about, such as death by sword, ball and shot.

Orr’s experiences in the run-up to (and limp down from) Waterloo are mainly recounted through the regimental records and graphic memoirs of others who were present. Coincidentally, the moment when the Black Watch stood at bay during the Battle of Quatre Bras (below) was painted later by William Barnes Wollen, whose depiction of Mary Queen of Scots on the Royal Mile features on the front cover of Spurtle’s Issue 345.

Wounded at the knee, Orr was pensioned off on half-pay in 1816. He served off and on in the ‘occupation’ of Ireland, but struggled unsuccessfully to find a fighting commission suited to his skill and inclinations in the drastically reduced peacetime Army that followed Bonaparte’s defeat.

He and his wife Jean Pollok were fortunate to enjoy the support of Lieutenant Colonel Macdonald, on whose estate they resided from 1821–24, at East Powderhall House, north of Edinburgh. The name will be familiar to Broughton readers. It was under Macdonald’s command that he re-enrolled in the Edinburgh Militia in 1831.

At this point, MacPhail’s narrative turns to the history of the recently established Scottish Naval and Military Academy. It had begun well in Waterloo Place, but after its move to George Street the morale of its principal teacher and the discipline of its boys collapsed, to the detriment of their education and the inconvenience of pedestrians passing on the street below.

Following a peculiarly Edinburgh stramash involving backstabbing, intrigue, pomposity and poor journalism (MacPhail is excellent at unpicking and explaining this), Orr was appointed Superintendent of the Academy, his brief being to lead it with a firm hand. This he did successfully until the institution’s closure in 1858. He died aged 89 and, like his friend Macdonald, is buried in Warriston Cemetery.

MacPhail tells these stories and more in elegant prose with assured scholarship. She supplements Orr’s own accounts with well-chosen contemporary memoirs by others, and her book benefits from generous colour plates of her subject’s uniform and personal memorabilia. It will appeal to anyone interested in Wellington’s roller-coaster campaigns through Iberia, and to those amused by the soft underbelly of 19th-century Edinburgh.–AM

Rosslyn MacPhail, From Fighting Napoleon to the Scottish Military Academy, ISBN 9781399034449, 232 pp., £25, Pen and Sword Military.